The post How to format your MLA Works Cited page appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>Like the rest of an MLA format paper, the Works Cited should be left-aligned and double-spaced with 1-inch margins.

You can use the free Scribbr Citation Generator to create and manage your Works Cited list. Choose your source type and enter the URL, DOI or title to get started.

Generate accurate MLA citations with Scribbr

Formatting the Works Cited page

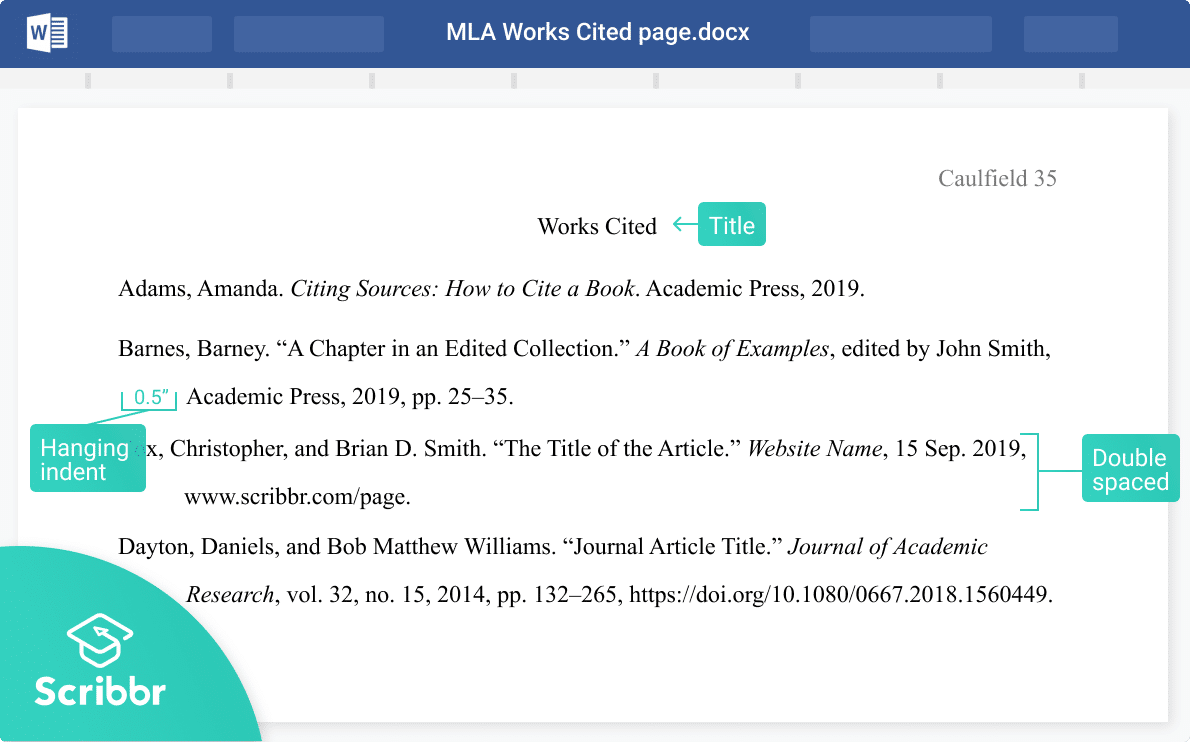

The Works Cited appears at the end of your paper. The layout is similar to the rest of an MLA format paper:

- Title the page Works Cited, centered and in plain text (no italics, bold, or underline).

- Alphabetize the entries by the author’s last name.

- Use left alignment and double line spacing (no extra space between entries).

- Use a hanging indent on entries that run over onto additional lines.

- Include a header with your last name and the page number in the top right corner.

Creating a hanging indent

If an entry is more than one line long, each line after the first must be indented 0.5 inches. This is called a hanging indent, and it helps the reader see where one entry ends and the next begins.

In Microsoft Word, you can create a hanging indent on all entries at once.

- Highlight the whole list and right click to open the Paragraph options.

- Under Indentation > Special, choose Hanging from the drop-down menu.

- Set the indent to 0.5 inches or 1.27cm.

If you’re using Google Docs, the steps are slightly different.

- Highlight the whole list and click on Format > Align and indent > Indentation options.

- Under Special indent, choose Hanging from the dropdown menu.

- Set the indent to 0.5 inches or 1.27cm.

You can also use our free template to create your Works Cited page in Microsoft Word or Google Docs.

Download Word template Copy Google Docs template

Examples of Works Cited entries

MLA provides nine core elements that you can use to build a reference for any source. Mouse over the example below to see how they work.

You only include the elements that are relevant to the type of source you’re citing.

Use the interactive tool to see different versions of an MLA Works Cited entry.

Examples for common source types

Book

The main elements of a book citation are the author, title (italicized), publisher, and year.

- Morrison, Toni. The Bluest Eye. Vintage International, 2007.

If there are other contributors (such as editors or translators), or if you consulted a particular volume or edition of a book, these elements should also be included in the citation.

Book chapter

If a book is a collection of chapters by different authors, you should cite the author and title of the specific work. The container gives details of the book, and the location is the page range on which the chapter appears.

- Andrews, Kehinde. “The Challenge for Black Studies in the Neoliberal University.” Decolonising the University, edited by Gurminder K. Bhambra et al., Pluto Press, 2018, pp. 149–144.

This format also applies to works collected in anthologies (such as poems, plays, or stories).

Journal article

Journals usually have volume and issue numbers, but no publisher is required. If you accessed the article through a database, this is included as a second container. The DOI provides a stable link to the article.

- Salenius, Sirpa. “Marginalized Identities and Spaces: James Baldwin’s Harlem, New York.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 48, no. 8, Jul. 2016, pp. 883–902. Sage Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934716658862.

If there is no DOI, look for a stable URL or permalink instead. Omit the “https://” prefix if using a URL or permalink, but always include it with a DOI.

Website

For websites (including online newspapers and magazines), you usually don’t have to include a publisher. The URL is included, with the “https://” prefix removed. If a web page has no publication date, add an access date instead.

- Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic, Jun. 2014, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

If a web page has no publication date, add an access date instead.

More MLA citation examples

We also have examples for a wide range of other source types.

Play | Poem | Short story | Movie | YouTube video | Newspaper | Interview | Lecture | PowerPoint Image | Song | Podcast | TV show | PDF | TED Talk | Bible | Shakespeare | Constitution

Authors and titles in the Works Cited list

There are a few important formatting rules when writing author names and titles in your Works Cited entries.

Author names

Author names are inverted in the Works Cited list. However, when a second author is listed, their name is not inverted. When a source has three or more authors, only the first author is listed, followed by “et al.” (Latin for “and others”). A corporate author may sometimes be listed instead of an individual.

- Smith, John.

- Smith, John, and David Jones.

- Smith, John, et al.

- Scribbr.

When no author is listed for a source, the Works Cited entry instead begins with the source title. The in-text citation should always match the first element of the Works Cited entry, so in these cases, it begins with the title (shortened if necessary) instead of the author’s last name.

Oxford Classical Dictionary. 4th ed., Oxford UP, 2012.

(Oxford Classical Dictionary)

Source and container titles

The titles of sources and containers are always written in title case (all major words capitalized).

Sources that are part of a larger work (e.g. a chapter in a book, an article in a periodical, a page on a website) are enclosed in quotation marks. The titles of self-contained sources (e.g. a book, a movie, a periodical, a website) are instead italicized. A title in the container position is always italicized.

If a source has no title, provide a description of the source instead. Only the first word of this description is capitalized, and no italics or quotation marks are used.

- Kafka, Franz. “The Metamorphosis.” The Metamorphosis and Other Stories, . . .

- Eliot, George. Middlemarch. . . .

- Mackintosh, Charles Rennie. Chair of stained oak. . . .

Ordering the list of Works Cited

Arrange the entries in your Works Cited list alphabetically by the author’s last name. See here for information on formatting annotations in an MLA annotated bibliography.

Multiple sources by the same author(s)

If your Works Cited list includes more than one work by a particular author, arrange these sources alphabetically by title. In place of the author element, write three em dashes for each source listed after the first.

———. “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic, Jun. 2014, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

———. The Water Dancer. One World, 2019.

The same applies to works by the same group of authors; replace the author element with three em dashes for subsequent sources.

Note, however, that two sources by “Smith, John, et al.” aren’t necessarily by the exact same authors; the authors represented by “et al.” could be different. Only use the three em dashes if the group of authors is exactly the same in each case; otherwise, repeat the author name and “et al.”

One author in combination with different coauthors

Sometimes, multiple entries will start with the same author, but in combination with different coauthors. Works by the author alone should come first, then works by two authors, and finally works by three or more authors (i.e., entries containing “et al.”).

Within this, sources with two authors are alphabetized by the second author’s last name, while sources using “et al.” are instead alphabetized by the title of the source.

Smith, John, and Emma Jones. . . .

Smith, John, and David Wilson. . . .

Smith, John, et al. . . .

Sources with no author

If there is no author, alphabetize the source based on the title of the work. Ignore articles (the, a, and an) for the purposes of alphabetization. If a title begins with a number, alphabetize it as you would if the number was spelled out.

Frequently asked questions about the Works Cited

- What goes in an MLA Works Cited list?

-

The MLA Works Cited lists every source that you cited in your paper. Each entry contains the author, title, and publication details of the source.

- How should I format the Works Cited page?

-

According to MLA format guidelines, the Works Cited page(s) should look like this:

- Running head containing your surname and the page number.

- The title, Works Cited, centered and in plain text.

- List of sources alphabetized by the author’s surname.

- Left-aligned.

- Double-spaced.

- 1-inch margins.

- Hanging indent applied to all entries.

- How do I apply a hanging indent?

-

To apply a hanging indent to your reference list or Works Cited list in Word or Google Docs, follow the steps below.

Microsoft Word:

- Highlight the whole list and right click to open the Paragraph options.

- Under Indentation > Special, choose Hanging from the dropdown menu.

- Set the indent to 0.5 inches or 1.27cm.

Google Docs:

- Highlight the whole list and click on Format > Align and indent > Indentation options.

- Under Special indent, choose Hanging from the dropdown menu.

- Set the indent to 0.5 inches or 1.27cm.

When the hanging indent is applied, for each reference, every line except the first is indented. This helps the reader see where one entry ends and the next begins.

- What information do I need to include in an MLA Works Cited entry?

-

A standard MLA Works Cited entry is structured as follows:

Author. “Title of the Source.” Title of the Container, Other contributors, Version, Number, Publisher, Publication date, Location.Only include information that is available for and relevant to your source.

- Are titles capitalized in MLA?

-

Yes. MLA style uses title case, which means that all principal words (nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and some conjunctions) are capitalized.

This applies to titles of sources as well as the title of, and subheadings in, your paper. Use MLA capitalization style even when the original source title uses different capitalization.

- What is the easiest way to create MLA citations?

-

The fastest and most accurate way to create MLA citations is by using Scribbr’s MLA Citation Generator.

Search by book title, page URL or journal DOI to automatically generate flawless citations, or cite manually using the simple citation forms.

The post How to format your MLA Works Cited page appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>The post How to write and format an APA abstract appeared first on Scribbr.

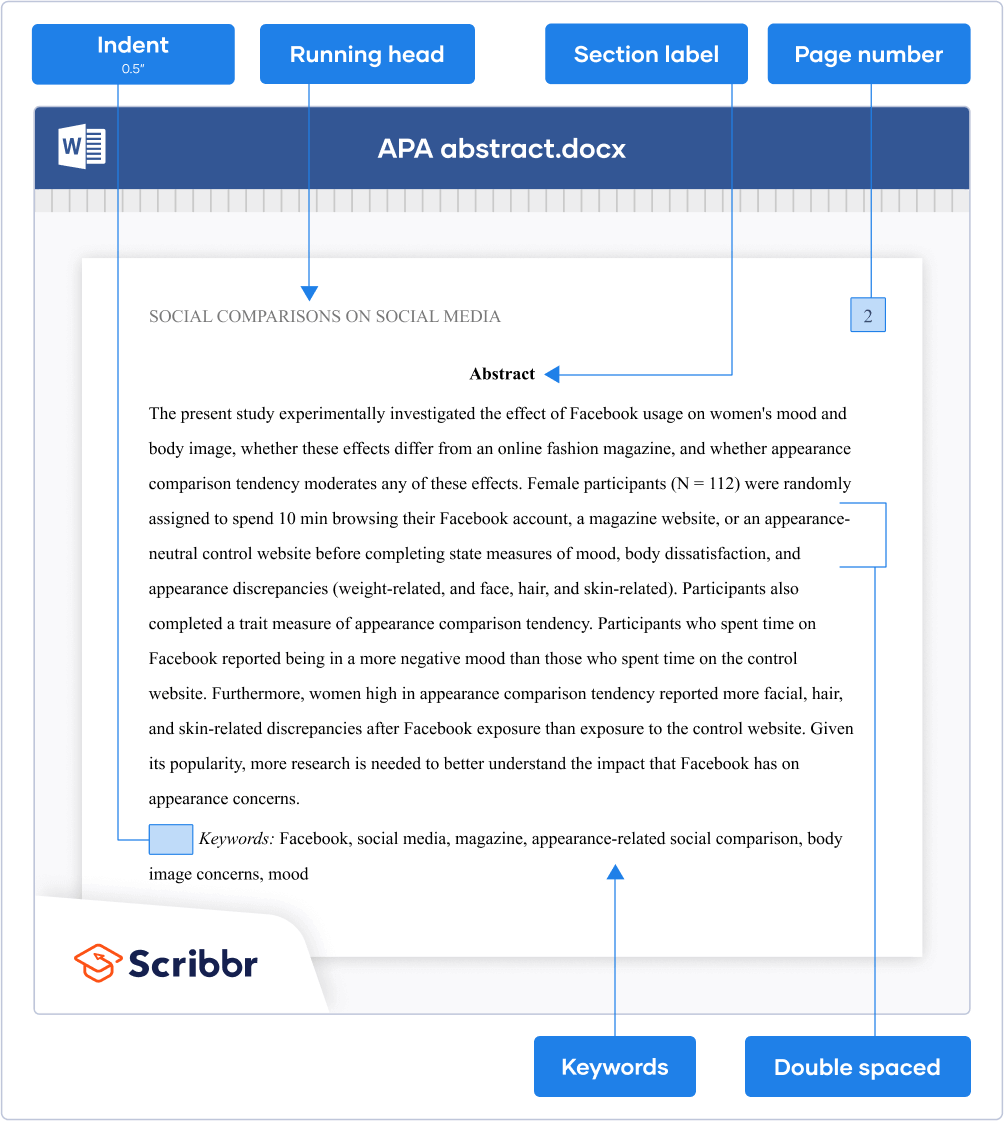

]]>An APA abstract is a comprehensive summary of your paper in which you briefly address the research problem, hypotheses, methods, results, and implications of your research. It’s placed on a separate page right after the title page and is usually no longer than 250 words.

Most professional papers that are submitted for publication require an abstract. Student papers typically don’t need an abstract, unless instructed otherwise.

How to format the abstract

APA abstract example

Formatting instructions

Follow these five steps to format your abstract in APA Style:

- Insert a running head (for a professional paper—not needed for a student paper) and page number.

- Set page margins to 1 inch (2.54 cm).

- Write “Abstract” (bold and centered) at the top of the page.

- Place the contents of your abstract on the next line.

- Do not indent the first line.

- Double-space the text.

- Use a legible font like Times New Roman (12 pt.).

- Limit the length to 250 words.

- List 3–5 keywords directly below the content.

- Indent the first line 0.5 inches.

- Write the label “Keywords:” (italicized).

- Write keywords in lowercase letters.

- Separate keywords with commas.

- Do not use a period after the keywords.

How to write an APA abstract

The abstract is a self-contained piece of text that informs the reader what your research is about. It’s best to write the abstract after you’re finished with the rest of your paper.

The questions below may help structure your abstract. Try answering them in one to three sentences each.

- What is the problem? Outline the objective, research questions, and/or hypotheses.

- What has been done? Explain your research methods.

- What did you discover? Summarize the key findings and conclusions.

- What do the findings mean? Summarize the discussion and recommendations.

Check out our guide on how to write an abstract for more guidance and an annotated example.

Which keywords to use

At the end of the abstract, you may include a few keywords that will be used for indexing if your paper is published on a database. Listing your keywords will help other researchers find your work.

Choosing relevant keywords is essential. Try to identify keywords that address your topic, method, or population. APA recommends including three to five keywords.

Keywords: Facebook, social media, magazine, appearance-related social comparison, body image concerns, mood.

Frequently asked questions

- What is the purpose of an abstract?

-

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

- How long should an APA abstract be?

-

An APA abstract is around 150–250 words long. However, always check your target journal’s guidelines and don’t exceed the specified word count.

- Where does the abstract go in an APA paper?

-

In an APA Style paper, the abstract is placed on a separate page after the title page (page 2).

- Can you cite sources in an abstract?

-

Avoid citing sources in your abstract. There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The post How to write and format an APA abstract appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>The post How to structure an essay: Templates and tips appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>This article provides useful templates and tips to help you outline your essay, make decisions about your structure, and organize your text logically.

The basics of essay structure

There are two main things to keep in mind when working on your essay structure: making sure to include the right information in each part, and deciding how you’ll organize the information within the body.

Parts of an essay

The three parts that make up all essays are described in the table below.

| Part | Content |

|---|---|

| Introduction |

|

| Body |

|

| Conclusion |

|

Order of information

You’ll also have to consider how to present information within the body. There are a few general principles that can guide you here.

The first is that your argument should move from the simplest claim to the most complex. The body of a good argumentative essay often begins with simple and widely accepted claims, and then moves towards more complex and contentious ones.

For example, you might begin by describing a generally accepted philosophical concept, and then apply it to a new topic. The grounding in the general concept will allow the reader to understand your unique application of it.

The second principle is that background information should appear towards the beginning of your essay. General background is presented in the introduction. If you have additional background to present, this information will usually come at the start of the body.

The third principle is that everything in your essay should be relevant to the thesis. Ask yourself whether each piece of information advances your argument or provides necessary background. And make sure that the text clearly expresses each piece of information’s relevance.

The sections below present several organizational templates for essays: the chronological approach, the compare-and-contrast approach, and the problems-methods-solutions approach.

Chronological structure

The chronological approach (sometimes called the cause-and-effect approach) is probably the simplest way to structure an essay. It just means discussing events in the order in which they occurred, discussing how they are related (i.e. the cause and effect involved) as you go.

A chronological approach can be useful when your essay is about a series of events. Don’t rule out other approaches, though—even when the chronological approach is the obvious one, you might be able to bring out more with a different structure.

Explore the tabs below to see a general template and a specific example outline from an essay on the invention of the printing press.

Compare-and-contrast structure

Essays with two or more main subjects are often structured around comparing and contrasting. For example, a literary analysis essay might compare two different texts, and an argumentative essay might compare the strengths of different arguments.

There are two main ways of structuring a compare-and-contrast essay: the alternating method, and the block method.

Alternating

In the alternating method, each paragraph compares your subjects in terms of a specific point of comparison. These points of comparison are therefore what defines each paragraph.

The tabs below show a general template for this structure, and a specific example for an essay comparing and contrasting distance learning with traditional classroom learning.

Block

In the block method, each subject is covered all in one go, potentially across multiple paragraphs. For example, you might write two paragraphs about your first subject and then two about your second subject, making comparisons back to the first.

The tabs again show a general template, followed by another essay on distance learning, this time with the body structured in blocks.

Problems-methods-solutions structure

An essay that concerns a specific problem (practical or theoretical) may be structured according to the problems-methods-solutions approach.

This is just what it sounds like: You define the problem, characterize a method or theory that may solve it, and finally analyze the problem, using this method or theory to arrive at a solution. If the problem is theoretical, the solution might be the analysis you present in the essay itself; otherwise, you might just present a proposed solution.

The tabs below show a template for this structure and an example outline for an essay about the problem of fake news.

Signposting to clarify your structure

Signposting means guiding the reader through your essay with language that describes or hints at the structure of what follows. It can help you clarify your structure for yourself as well as helping your reader follow your ideas.

The essay overview

In longer essays whose body is split into multiple named sections, the introduction often ends with an overview of the rest of the essay. This gives a brief description of the main idea or argument of each section.

The overview allows the reader to immediately understand what will be covered in the essay and in what order. Though it describes what comes later in the text, it is generally written in the present tense. The following example is from a literary analysis essay on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Transitions

Transition words and phrases are used throughout all good essays to link together different ideas. They help guide the reader through your text, and an essay that uses them effectively will be much easier to follow.

Various different relationships can be expressed by transition words, as shown in this example.

Transition sentences may be included to transition between different paragraphs or sections of an essay. A good transition sentence moves the reader on to the next topic while indicating how it relates to the previous one.

Frequently asked questions about essay structure

- What is the structure of an essay?

-

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement, a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

- Why is structure important in an essay?

-

An essay isn’t just a loose collection of facts and ideas. Instead, it should be centered on an overarching argument (summarized in your thesis statement) that every part of the essay relates to.

The way you structure your essay is crucial to presenting your argument coherently. A well-structured essay helps your reader follow the logic of your ideas and understand your overall point.

- How do I compare and contrast in a structured way?

-

Comparisons in essays are generally structured in one of two ways:

- The alternating method, where you compare your subjects side by side according to one specific aspect at a time.

- The block method, where you cover each subject separately in its entirety.

It’s also possible to combine both methods, for example by writing a full paragraph on each of your topics and then a final paragraph contrasting the two according to a specific metric.

- Do I have to stick to my essay outline as I write?

-

You should try to follow your outline as you write your essay. However, if your ideas change or it becomes clear that your structure could be better, it’s okay to depart from your essay outline. Just make sure you know why you’re doing so.

The post How to structure an essay: Templates and tips appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>The post The four main types of essay | Quick guide with examples appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>Argumentative and expository essays are focused on conveying information and making clear points, while narrative and descriptive essays are about exercising creativity and writing in an interesting way. At university level, argumentative essays are the most common type.

| Essay type | Skills tested | Example prompt |

|---|---|---|

| Argumentative |

|

Has the rise of the internet had a positive or negative impact on education? |

| Expository |

|

Explain how the invention of the printing press changed European society in the 15th century. |

| Narrative |

|

Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself. |

| Descriptive |

|

Describe an object that has sentimental value for you. |

In high school and college, you will also often have to write textual analysis essays, which test your skills in close reading and interpretation.

Argumentative essays

An argumentative essay presents an extended, evidence-based argument. It requires a strong thesis statement—a clearly defined stance on your topic. Your aim is to convince the reader of your thesis using evidence (such as quotations) and analysis.

Argumentative essays test your ability to research and present your own position on a topic. This is the most common type of essay at college level—most papers you write will involve some kind of argumentation.

The essay is divided into an introduction, body, and conclusion:

- The introduction provides your topic and thesis statement

- The body presents your evidence and arguments

- The conclusion summarizes your argument and emphasizes its importance

The example below is a paragraph from the body of an argumentative essay about the effects of the internet on education. Mouse over it to learn more.

Expository essays

An expository essay provides a clear, focused explanation of a topic. It doesn’t require an original argument, just a balanced and well-organized view of the topic.

Expository essays test your familiarity with a topic and your ability to organize and convey information. They are commonly assigned at high school or in exam questions at college level.

The introduction of an expository essay states your topic and provides some general background, the body presents the details, and the conclusion summarizes the information presented.

A typical body paragraph from an expository essay about the invention of the printing press is shown below. Mouse over it to learn more.

Narrative essays

A narrative essay is one that tells a story. This is usually a story about a personal experience you had, but it may also be an imaginative exploration of something you have not experienced.

Narrative essays test your ability to build up a narrative in an engaging, well-structured way. They are much more personal and creative than other kinds of academic writing. Writing a personal statement for an application requires the same skills as a narrative essay.

A narrative essay isn’t strictly divided into introduction, body, and conclusion, but it should still begin by setting up the narrative and finish by expressing the point of the story—what you learned from your experience, or why it made an impression on you.

Mouse over the example below, a short narrative essay responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” to explore its structure.

Descriptive essays

A descriptive essay provides a detailed sensory description of something. Like narrative essays, they allow you to be more creative than most academic writing, but they are more tightly focused than narrative essays. You might describe a specific place or object, rather than telling a whole story.

Descriptive essays test your ability to use language creatively, making striking word choices to convey a memorable picture of what you’re describing.

A descriptive essay can be quite loosely structured, though it should usually begin by introducing the object of your description and end by drawing an overall picture of it. The important thing is to use careful word choices and figurative language to create an original description of your object.

Mouse over the example below, a response to the prompt “Describe a place you love to spend time in,” to learn more about descriptive essays.

Textual analysis essays

Though every essay type tests your writing skills, some essays also test your ability to read carefully and critically. In a textual analysis essay, you don’t just present information on a topic, but closely analyze a text to explain how it achieves certain effects.

Rhetorical analysis

A rhetorical analysis looks at a persuasive text (e.g. a speech, an essay, a political cartoon) in terms of the rhetorical devices it uses, and evaluates their effectiveness.

The goal is not to state whether you agree with the author’s argument but to look at how they have constructed it.

The introduction of a rhetorical analysis presents the text, some background information, and your thesis statement; the body comprises the analysis itself; and the conclusion wraps up your analysis of the text, emphasizing its relevance to broader concerns.

The example below is from a rhetorical analysis of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Mouse over it to learn more.

Literary analysis

A literary analysis essay presents a close reading of a work of literature—e.g. a poem or novel—to explore the choices made by the author and how they help to convey the text’s theme. It is not simply a book report or a review, but an in-depth interpretation of the text.

Literary analysis looks at things like setting, characters, themes, and figurative language. The goal is to closely analyze what the author conveys and how.

The introduction of a literary analysis essay presents the text and background, and provides your thesis statement; the body consists of close readings of the text with quotations and analysis in support of your argument; and the conclusion emphasizes what your approach tells us about the text.

Mouse over the example below, the introduction to a literary analysis essay on Frankenstein, to learn more.

Frequently asked questions about types of essays

- How do I know what type of essay to write?

-

At high school and in composition classes at university, you’ll often be told to write a specific type of essay, but you might also just be given prompts.

Look for keywords in these prompts that suggest a certain approach: The word “explain” suggests you should write an expository essay, while the word “describe” implies a descriptive essay. An argumentative essay might be prompted with the word “assess” or “argue.”

- What type of essay is most common at university?

-

The vast majority of essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay. Almost all academic writing involves building up an argument, though other types of essay might be assigned in composition classes.

Essays can present arguments about all kinds of different topics. For example:

- In a literary analysis essay, you might make an argument for a specific interpretation of a text

- In a history essay, you might present an argument for the importance of a particular event

- In a politics essay, you might argue for the validity of a certain political theory

- What’s the difference between an expository essay and an argumentative essay?

-

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

- What’s the difference between a narrative essay and a descriptive essay?

-

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays, and similar writing skills can apply to both.

The post The four main types of essay | Quick guide with examples appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>The post How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>A rhetorical analysis is structured similarly to other essays: an introduction presenting the thesis, a body analyzing the text directly, and a conclusion to wrap up. This article defines some key rhetorical concepts and provides tips on how to write a rhetorical analysis.

Key concepts in rhetoric

Rhetoric, the art of effective speaking and writing, is a subject that trains you to look at texts, arguments and speeches in terms of how they are designed to persuade the audience. This section introduces a few of the key concepts of this field.

Appeals: Logos, ethos, pathos

Appeals are how the author convinces their audience. Three central appeals are discussed in rhetoric, established by the philosopher Aristotle and sometimes called the rhetorical triangle: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Logos, or the logical appeal, refers to the use of reasoned argument to persuade. This is the dominant approach in academic writing, where arguments are built up using reasoning and evidence.

Ethos, or the ethical appeal, involves the author presenting themselves as an authority on their subject. For example, someone making a moral argument might highlight their own morally admirable behavior; someone speaking about a technical subject might present themselves as an expert by mentioning their qualifications.

Pathos, or the pathetic appeal, evokes the audience’s emotions. This might involve speaking in a passionate way, employing vivid imagery, or trying to provoke anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response in the audience.

These three appeals are all treated as integral parts of rhetoric, and a given author may combine all three of them to convince their audience.

Text and context

In rhetoric, a text is not necessarily a piece of writing (though it may be this). A text is whatever piece of communication you are analyzing. This could be, for example, a speech, an advertisement, or a satirical image.

In these cases, your analysis would focus on more than just language—you might look at visual or sonic elements of the text too.

The context is everything surrounding the text: Who is the author (or speaker, designer, etc.)? Who is their (intended or actual) audience? When and where was the text produced, and for what purpose?

Looking at the context can help to inform your rhetorical analysis. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech has universal power, but the context of the civil rights movement is an important part of understanding why.

Claims, supports, and warrants

A piece of rhetoric is always making some sort of argument, whether it’s a very clearly defined and logical one (e.g. in a philosophy essay) or one that the reader has to infer (e.g. in a satirical article). These arguments are built up with claims, supports, and warrants.

A claim is the fact or idea the author wants to convince the reader of. An argument might center on a single claim, or be built up out of many. Claims are usually explicitly stated, but they may also just be implied in some kinds of text.

The author uses supports to back up each claim they make. These might range from hard evidence to emotional appeals—anything that is used to convince the reader to accept a claim.

The warrant is the logic or assumption that connects a support with a claim. Outside of quite formal argumentation, the warrant is often unstated—the author assumes their audience will understand the connection without it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still explore the implicit warrant in these cases.

For example, look at the following statement:

We can see a claim and a support here, but the warrant is implicit. Here, the warrant is the assumption that more likeable candidates would have inspired greater turnout. We might be more or less convinced by the argument depending on whether we think this is a fair assumption.

Analyzing the text

Rhetorical analysis isn’t a matter of choosing concepts in advance and applying them to a text. Instead, it starts with looking at the text in detail and asking the appropriate questions about how it works:

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Do they focus closely on their key claims, or do they discuss various topics?

- What tone do they take—angry or sympathetic? Personal or authoritative? Formal or informal?

- Who seems to be the intended audience? Is this audience likely to be successfully reached and convinced?

- What kinds of evidence are presented?

By asking these questions, you’ll discover the various rhetorical devices the text uses. Don’t feel that you have to cram in every rhetorical term you know—focus on those that are most important to the text.

The following sections show how to write the different parts of a rhetorical analysis.

Introducing your rhetorical analysis

Like all essays, a rhetorical analysis begins with an introduction. The introduction tells readers what text you’ll be discussing, provides relevant background information, and presents your thesis statement.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how an introduction works.

The body: Doing the analysis

The body of your rhetorical analysis is where you’ll tackle the text directly. It’s often divided into three paragraphs, although it may be more in a longer essay.

Each paragraph should focus on a different element of the text, and they should all contribute to your overall argument for your thesis statement.

Hover over the example to explore how a typical body paragraph is constructed.

Concluding a rhetorical analysis

The conclusion of a rhetorical analysis wraps up the essay by restating the main argument and showing how it has been developed by your analysis. It may also try to link the text, and your analysis of it, with broader concerns.

Explore the example below to get a sense of the conclusion.

Frequently asked questions about rhetorical analysis

- What’s the goal of a rhetorical analysis?

-

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay, it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

- What counts as a text for rhetorical analysis?

-

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

- What are logos, ethos, and pathos?

-

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments. Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle. They are central to rhetorical analysis, though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

- What are claims, supports, and warrants?

-

In rhetorical analysis, a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

The post How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>The post Comparing and contrasting in an essay | Tips & examples appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>You might find yourself comparing all kinds of things in an academic essay: historical figures, literary works, policies, research methods, etc. Doing so is an important part of constructing arguments.

When should I compare and contrast?

Many assignments will invite you to make comparisons quite explicitly, as in these prompts.

- Compare the treatment of the theme of beauty in the poetry of William Wordsworth and John Keats.

- Compare and contrast in-class and distance learning. What are the advantages and disadvantages of each approach?

Some other prompts may not directly ask you to compare and contrast, but present you with a topic where comparing and contrasting could be a good approach.

One way to approach this essay might be to contrast the situation before the Great Depression with the situation during it, to highlight how large a difference it made.

Comparing and contrasting is also used in all kinds of academic contexts where it’s not explicitly prompted. For example, a literature review involves comparing and contrasting different studies on your topic, and an argumentative essay may involve weighing up the pros and cons of different arguments.

Making effective comparisons

As the name suggests, comparing and contrasting is about identifying both similarities and differences. You might focus on contrasting quite different subjects or comparing subjects with a lot in common—but there must be some grounds for comparison in the first place.

For example, you might contrast French society before and after the French Revolution; you’d likely find many differences, but there would be a valid basis for comparison. However, if you contrasted pre-revolutionary France with Han-dynasty China, your reader might wonder why you chose to compare these two societies.

This is why it’s important to clarify the point of your comparisons by writing a focused thesis statement. Every element of an essay should serve your central argument in some way. Consider what you’re trying to accomplish with any comparisons you make, and be sure to make this clear to the reader.

Comparing and contrasting as a brainstorming tool

Comparing and contrasting can be a useful tool to help organize your thoughts before you begin writing any type of academic text. You might use it to compare different theories and approaches you’ve encountered in your preliminary research, for example.

Let’s say your research involves the competing psychological approaches of behaviorism and cognitive psychology. You might make a table to summarize the key differences between them.

| Behaviorism | Cognitive psychology |

|---|---|

| Dominant from the 1920s to the 1950s | Rose to prominence in the 1960s |

| Mental processes cannot be empirically studied | Mental processes as focus of study |

| Focuses on how thinking is affected by conditioning and environment | Focuses on the cognitive processes themselves |

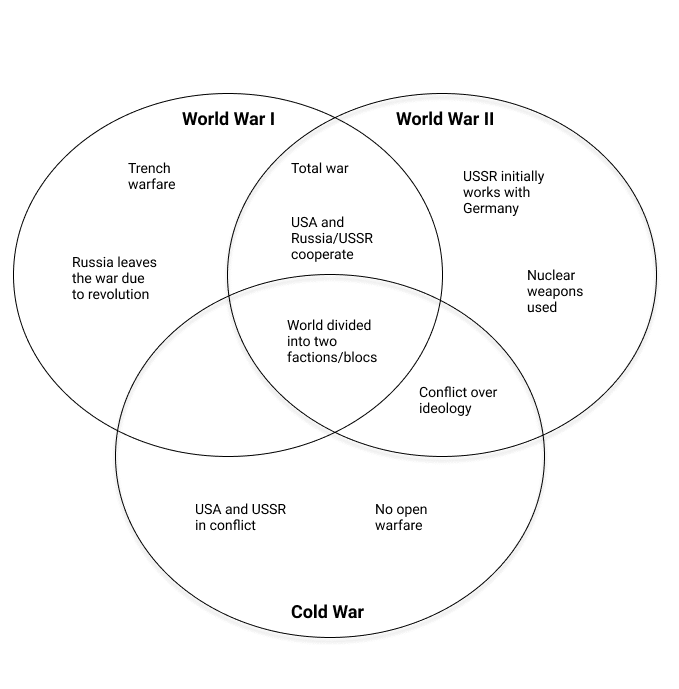

Or say you’re writing about the major global conflicts of the twentieth century. You might visualize the key similarities and differences in a Venn diagram.

These visualizations wouldn’t make it into your actual writing, so they don’t have to be very formal in terms of phrasing or presentation. The point of comparing and contrasting at this stage is to help you organize and shape your ideas to aid you in structuring your arguments.

Structuring your comparisons

When comparing and contrasting in an essay, there are two main ways to structure your comparisons: the alternating method and the block method.

The alternating method

In the alternating method, you structure your text according to what aspect you’re comparing. You cover both your subjects side by side in terms of a specific point of comparison. Your text is structured like this:

- Point of comparison A

- Subject 1

- Subject 2

- Point of comparison B

- Subject 1

- Subject 2

Mouse over the example paragraph below to see how this approach works.

The block method

In the block method, you cover each of the overall subjects you’re comparing in a block. You say everything you have to say about your first subject, then discuss your second subject, making comparisons and contrasts back to the things you’ve already said about the first. Your text is structured like this:

- Subject 1

- Point of comparison A

- Point of comparison B

- Subject 2

- Point of comparison A

- Point of comparison B

Mouse over the example paragraph below to see how this approach works.

Note that these two methods can be combined; these two example paragraphs could both be part of the same essay, but it’s wise to use an essay outline to plan out which approach you’re taking in each paragraph.

Frequently asked questions about comparing and contrasting

- When do I need to compare and contrast?

-

Some essay prompts include the keywords “compare” and/or “contrast.” In these cases, an essay structured around comparing and contrasting is the appropriate response.

Comparing and contrasting is also a useful approach in all kinds of academic writing: You might compare different studies in a literature review, weigh up different arguments in an argumentative essay, or consider different theoretical approaches in a theoretical framework.

- How do I choose subjects to compare and contrast?

-

Your subjects might be very different or quite similar, but it’s important that there be meaningful grounds for comparison. You can probably describe many differences between a cat and a bicycle, but there isn’t really any connection between them to justify the comparison.

You’ll have to write a thesis statement explaining the central point you want to make in your essay, so be sure to know in advance what connects your subjects and makes them worth comparing.

- How do I compare and contrast in a structured way?

-

Comparisons in essays are generally structured in one of two ways:

- The alternating method, where you compare your subjects side by side according to one specific aspect at a time.

- The block method, where you cover each subject separately in its entirety.

It’s also possible to combine both methods, for example by writing a full paragraph on each of your topics and then a final paragraph contrasting the two according to a specific metric.

The post Comparing and contrasting in an essay | Tips & examples appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>The post How to write a descriptive essay | Example & tips appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>Descriptive essays test your ability to use language in an original and creative way, to convey to the reader a memorable image of whatever you are describing. They are commonly assigned as writing exercises at high school and in composition classes.

Descriptive essay topics

When you are assigned a descriptive essay, you’ll normally be given a specific prompt or choice of prompts. They will often ask you to describe something from your own experience.

- Describe a place you love to spend time in.

- Describe an object that has sentimental value for you.

You might also be asked to describe something outside your own experience, in which case you’ll have to use your imagination.

- Describe the experience of a soldier in the trenches of World War I.

- Describe what it might be like to live on another planet.

Sometimes you’ll be asked to describe something more abstract, like an emotion.

If you’re not given a specific prompt, try to think of something you feel confident describing in detail. Think of objects and places you know well, that provoke specific feelings or sensations, and that you can describe in an interesting way.

Tips for writing descriptively

The key to writing an effective descriptive essay is to find ways of bringing your subject to life for the reader. You’re not limited to providing a literal description as you would be in more formal essay types.

Make use of figurative language, sensory details, and strong word choices to create a memorable description.

Use figurative language

Figurative language consists of devices like metaphor and simile that use words in non-literal ways to create a memorable effect. This is essential in a descriptive essay; it’s what gives your writing its creative edge and makes your description unique.

Take the following description of a park.

This tells us something about the place, but it’s a bit too literal and not likely to be memorable.

If we want to make the description more likely to stick in the reader’s mind, we can use some figurative language.

Here we have used a simile to compare the park to a face and the trees to facial hair. This is memorable because it’s not what the reader expects; it makes them look at the park from a different angle.

You don’t have to fill every sentence with figurative language, but using these devices in an original way at various points throughout your essay will keep the reader engaged and convey your unique perspective on your subject.

Use your senses

Another key aspect of descriptive writing is the use of sensory details. This means referring not only to what something looks like, but also to smell, sound, touch, and taste.

Obviously not all senses will apply to every subject, but it’s always a good idea to explore what’s interesting about your subject beyond just what it looks like.

Even when your subject is more abstract, you might find a way to incorporate the senses more metaphorically, as in this descriptive essay about fear.

Choose the right words

Writing descriptively involves choosing your words carefully. The use of effective adjectives is important, but so is your choice of adverbs, verbs, and even nouns.

It’s easy to end up using clichéd phrases—“cold as ice,” “free as a bird”—but try to reflect further and make more precise, original word choices. Clichés provide conventional ways of describing things, but they don’t tell the reader anything about your unique perspective on what you’re describing.

Try looking over your sentences to find places where a different word would convey your impression more precisely or vividly. Using a thesaurus can help you find alternative word choices.

- My cat runs across the garden quickly and jumps onto the fence to watch it from above.

- My cat crosses the garden nimbly and leaps onto the fence to survey it from above.

However, exercise care in your choices; don’t just look for the most impressive-looking synonym you can find for every word. Overuse of a thesaurus can result in ridiculous sentences like this one:

- My feline perambulates the allotment proficiently and capers atop the palisade to regard it from aloft.

Descriptive essay example

An example of a short descriptive essay, written in response to the prompt “Describe a place you love to spend time in,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how a descriptive essay works.

Frequently asked questions about descriptive essays

- What’s the difference between a narrative essay and a descriptive essay?

-

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays, and similar writing skills can apply to both.

- How do I come up with a topic for my descriptive essay?

-

If you’re not given a specific prompt for your descriptive essay, think about places and objects you know well, that you can think of interesting ways to describe, or that have strong personal significance for you.

The best kind of object for a descriptive essay is one specific enough that you can describe its particular features in detail—don’t choose something too vague or general.

The post How to write a descriptive essay | Example & tips appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>The post How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>Narrative essays test your ability to express your experiences in a creative and compelling way, and to follow an appropriate narrative structure. They are often assigned in high school or in composition classes at university. You can also use these techniques when writing a personal statement for an application.

What is a narrative essay for?

When assigned a narrative essay, you might find yourself wondering: Why does my teacher want to hear this story? Topics for narrative essays can range from the important to the trivial. Usually the point is not so much the story itself, but the way you tell it.

A narrative essay is a way of testing your ability to tell a story in a clear and interesting way. You’re expected to think about where your story begins and ends, and how to convey it with eye-catching language and a satisfying pace.

These skills are quite different from those needed for formal academic writing. For instance, in a narrative essay the use of the first person (“I”) is encouraged, as is the use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense.

Choosing a topic

Narrative essay assignments vary widely in the amount of direction you’re given about your topic. You may be assigned quite a specific topic or choice of topics to work with.

- Write a story about your first day of school.

- Write a story about your favorite holiday destination.

You may also be given prompts that leave you a much wider choice of topic.

- Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself.

- Write about an achievement you are proud of. What did you accomplish, and how?

In these cases, you might have to think harder to decide what story you want to tell. The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to talk about a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

For example, a trip where everything went according to plan makes for a less interesting story than one where something unexpected happened that you then had to respond to. Choose an experience that might surprise the reader or teach them something.

Narrative essays in college applications

When applying for college, you might be asked to write a narrative essay that expresses something about your personal qualities.

For example, this application prompt from Common App requires you to respond with a narrative essay.

In this context, choose a story that is not only interesting but also expresses the qualities the prompt is looking for—here, resilience and the ability to learn from failure—and frame the story in a way that emphasizes these qualities.

Interactive example of a narrative essay

An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works.

Frequently asked questions about narrative essays

- How do I come up with a topic for my narrative essay?

-

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

- When do I write a narrative essay?

-

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

- What’s the difference between a narrative essay and a descriptive essay?

-

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays, and similar writing skills can apply to both.

The post How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>The post How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>Argumentative essays are by far the most common type of essay to write at university.

When do you write an argumentative essay?

You might be assigned an argumentative essay as a writing exercise in high school or in a composition class. The prompt will often ask you to argue for one of two positions, and may include terms like “argue” or “argument.” It will frequently take the form of a question.

The prompt may also be more open-ended in terms of the possible arguments you could make.

Argumentative writing at college level

At university, the vast majority of essays or papers you write will involve some form of argumentation. For example, both rhetorical analysis and literary analysis essays involve making arguments about texts.

In this context, you won’t necessarily be told to write an argumentative essay—but making an evidence-based argument is an essential goal of most academic writing, and this should be your default approach unless you’re told otherwise.

Examples of argumentative essay prompts

At a university level, all the prompts below imply an argumentative essay as the appropriate response.

Your research should lead you to develop a specific position on the topic. The essay then argues for that position and aims to convince the reader by presenting your evidence, evaluation and analysis.

- Don’t just list all the effects you can think of.

- Do develop a focused argument about the overall effect and why it matters, backed up by evidence from sources.

- Don’t just provide a selection of data on the measures’ effectiveness.

- Do build up your own argument about which kinds of measures have been most or least effective, and why.

- Don’t just analyze a random selection of doppelgänger characters.

- Do form an argument about specific texts, comparing and contrasting how they express their thematic concerns through doppelgänger characters.

Approaches to argumentative essays

An argumentative essay should be objective in its approach; your arguments should rely on logic and evidence, not on exaggeration or appeals to emotion.

There are many possible approaches to argumentative essays, but there are two common models that can help you start outlining your arguments: The Toulmin model and the Rogerian model.

Toulmin arguments

The Toulmin model consists of four steps, which may be repeated as many times as necessary for the argument:

- Make a claim

- Provide the grounds (evidence) for the claim

- Explain the warrant (how the grounds support the claim)

- Discuss possible rebuttals to the claim, identifying the limits of the argument and showing that you have considered alternative perspectives

The Toulmin model is a common approach in academic essays. You don’t have to use these specific terms (grounds, warrants, rebuttals), but establishing a clear connection between your claims and the evidence supporting them is crucial in an argumentative essay.

Say you’re making an argument about the effectiveness of workplace anti-discrimination measures. You might:

- Claim that unconscious bias training does not have the desired results, and resources would be better spent on other approaches

- Cite data to support your claim

- Explain how the data indicates that the method is ineffective

- Anticipate objections to your claim based on other data, indicating whether these objections are valid, and if not, why not.

Rogerian arguments

The Rogerian model also consists of four steps you might repeat throughout your essay:

- Discuss what the opposing position gets right and why people might hold this position

- Highlight the problems with this position

- Present your own position, showing how it addresses these problems

- Suggest a possible compromise—what elements of your position would proponents of the opposing position benefit from adopting?

This model builds up a clear picture of both sides of an argument and seeks a compromise. It is particularly useful when people tend to disagree strongly on the issue discussed, allowing you to approach opposing arguments in good faith.

Say you want to argue that the internet has had a positive impact on education. You might:

- Acknowledge that students rely too much on websites like Wikipedia

- Argue that teachers view Wikipedia as more unreliable than it really is

- Suggest that Wikipedia’s system of citations can actually teach students about referencing

- Suggest critical engagement with Wikipedia as a possible assignment for teachers who are skeptical of its usefulness.

You don’t necessarily have to pick one of these models—you may even use elements of both in different parts of your essay—but it’s worth considering them if you struggle to structure your arguments.

Regardless of which approach you take, your essay should always be structured using an introduction, a body, and a conclusion.

Introducing your argument

Like other academic essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction. The introduction serves to capture the reader’s interest, provide background information, present your thesis statement, and (in longer essays) to summarize the structure of the body.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a typical introduction works.

The body: Developing your argument

The body of an argumentative essay is where you develop your arguments in detail. Here you’ll present evidence, analysis, and reasoning to convince the reader that your thesis statement is true.

In the standard five-paragraph format for short essays, the body takes up three of your five paragraphs. In longer essays, it will be more paragraphs, and might be divided into sections with headings.

Each paragraph covers its own topic, introduced with a topic sentence. Each of these topics must contribute to your overall argument; don’t include irrelevant information.

This example paragraph takes a Rogerian approach: It first acknowledges the merits of the opposing position and then highlights problems with that position.

Hover over different parts of the example to see how a body paragraph is constructed.

Concluding your argument

An argumentative essay ends with a conclusion that summarizes and reflects on the arguments made in the body.

No new arguments or evidence appear here, but in longer essays you may discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your argument and suggest topics for future research. In all conclusions, you should stress the relevance and importance of your argument.

Hover over the following example to see the typical elements of a conclusion.

Frequently asked questions about argumentative essays

- What’s the difference between an expository essay and an argumentative essay?

-

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

- When do I need to cite sources?

-

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays, research papers, and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote, paraphrase, or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA, MLA, and Chicago.

- When do I write an argumentative essay?

-

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay. Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

The post How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>The post How to write an expository essay appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>Expository essays are usually short assignments intended to test your composition skills or your understanding of a subject. They tend to involve less research and original arguments than argumentative essays.

When should you write an expository essay?

In school and university, you might have to write expository essays as in-class exercises, exam questions, or coursework assignments.

Sometimes it won’t be directly stated that the assignment is an expository essay, but there are certain keywords that imply expository writing is required. Consider the prompts below.

The word “explain” here is the clue: An essay responding to this prompt should provide an explanation of this historical process—not necessarily an original argument about it.

Sometimes you’ll be asked to define a particular term or concept. This means more than just copying down the dictionary definition; you’ll be expected to explore different ideas surrounding the term, as this prompt emphasizes.

How to approach an expository essay

An expository essay should take an objective approach: It isn’t about your personal opinions or experiences. Instead, your goal is to provide an informative and balanced explanation of your topic. Avoid using the first or second person (“I” or “you”).

The structure of your expository essay will vary according to the scope of your assignment and the demands of your topic. It’s worthwhile to plan out your structure before you start, using an essay outline.

A common structure for a short expository essay consists of five paragraphs: An introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Introducing your essay

Like all essays, an expository essay begins with an introduction. This serves to hook the reader’s interest, briefly introduce your topic, and provide a thesis statement summarizing what you’re going to say about it.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a typical introduction works.

Writing the body paragraphs

The body of your essay is where you cover your topic in depth. It often consists of three paragraphs, but may be more for a longer essay. This is where you present the details of the process, idea or topic you’re explaining.

It’s important to make sure each paragraph covers its own clearly defined topic, introduced with a topic sentence. Different topics (all related to the overall subject matter of the essay) should be presented in a logical order, with clear transitions between paragraphs.

Hover over different parts of the example paragraph below to see how a body paragraph is constructed.

Concluding your essay

The conclusion of an expository essay serves to summarize the topic under discussion. It should not present any new information or evidence, but should instead focus on reinforcing the points made so far. Essentially, your conclusion is there to round off the essay in an engaging way.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a conclusion works.

Frequently asked questions about expository essays

- How long is an expository essay?

-

An expository essay is a broad form that varies in length according to the scope of the assignment.

Expository essays are often assigned as a writing exercise or as part of an exam, in which case a five-paragraph essay of around 800 words may be appropriate.

You’ll usually be given guidelines regarding length; if you’re not sure, ask.

- When do I write an expository essay?

-

An expository essay is a common assignment in high-school and university composition classes. It might be assigned as coursework, in class, or as part of an exam.

Sometimes you might not be told explicitly to write an expository essay. Look out for prompts containing keywords like “explain” and “define.” An expository essay is usually the right response to these prompts.

- What’s the difference between an expository essay and an argumentative essay?

-

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

The post How to write an expository essay appeared first on Scribbr.

]]>